| Camden’s Roundhouse was recently home to Utopia, a reimagined sensory city experienced through a series of walk-through environments. Created by filmmaker, writer and artist Penny Woolcock and renowned Glastonbury Festival stage designers Block 9, the series of installations, projections and sound pieces brought to our attention the substance of the city; the voices that we would otherwise miss. Recognising that ‘most of the time we just pass each other’, Woolcock spoke to a number of Londoners about their lives and experiences, encouraging them ‘to tell stories which were unique to them, but somehow told a bigger truth’. With an overwhelming number of voices combining to disorientate the senses, visitors had to get close to each speaker, and give the stranger’s voice their undivided attention; quite uncommon for London. |

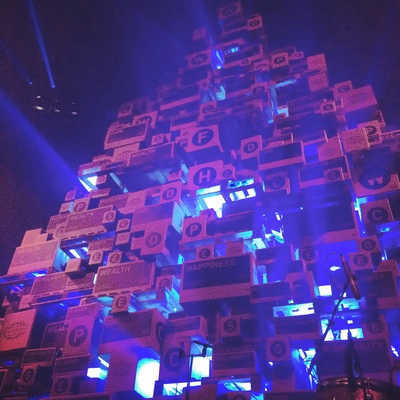

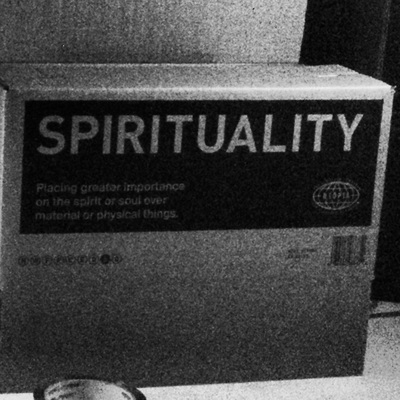

Whilst the word ‘community' might have utopian principles at its core, Woolcock’s ‘Utopia’ was true to life, exposing the disparity between rich and poor, and the relationship between greed and poverty. She showcased the truth; that money is the main objective for most people, resulting in superficial values. The cardboard boxes piled in a pyramid formation in the main room spoke of such values: wealth, desirability, fame, glamour, spirituality, popularity, cool, exclusivity and happiness. Utopian researcher Ruth Levitas believes that ‘the spirit of utopia is the pursuit of happiness’, but here Woolcock exposed the apparent dystopia in the perceived utopian dream by demonstrating the superficiality of values packaged up and available for purchase; the building blocks of our capitalist, consumer-driven world. As the old saying goes, money can’t buy happiness but the truth is that we all live by the belief that it can. The belief seeps into so many of our experiences; the radio has us singing that we ‘wanna be a billionaire so frickin’ bad’ at the same time as making it commonplace to have ‘money on my mind'. The voice of one Londoner in ‘Utopia’ declared that ‘money is the main goal...when we have money we feel successful’, and the scramble to achieve it was portrayed in the pandemonium and somewhat post-apocalyptic arrangement of the exhibition.

As you entered the main space sounds reverberating from the projection to the left were disorienting, words crackled around you: ‘moneymaking is all around’, ‘advertising stuff’, ‘money, money, money’. One rioter explained the desire for Nike trainers, and the reality of the situation 4 years ago ‘I can’t afford it and the shop doors were open…’ providing an insight into the minds of the rioters. Another explained the reality of society ‘some people are destined to commit crimes…you create thieves and then punish them for stealing’. At Utopia Live Lates, Arlene Phillips CBE stated that ‘money has become the biggest God on earth’, and it would seem she isn’t too far from the truth.

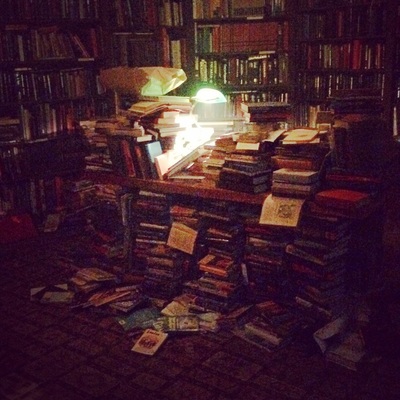

Utopian thinker William Morris believed that art was ‘the central battleground in the warfare of his age’ and I think that this notion was at play at the Roundhouse. Philosophy was at the heart of the exhibition - not only did its title derive from philosophical roots - but the likes of More’s Utopia and Plato’s Republic could be found in the ransacked library room, and readings from them were heard amongst the many voices. One Londoner spoke of how reading Plato changed his perspective on life after his involvement in the London riots.

Woolcock believes that ‘art is not just decoration…but absolutely central to who we are as human beings’ and her work at the Roundhouse exemplified this. She allowed Londoners to disclose everything - their sex lives, their class and their attitude towards other classes, their depression, their thoughts on gentrification, their experiences of racism, their anxieties, their childhood, the reality of being bullied, their education failures, their shoplifting tales and their laughter. Her work is a critique of our present situation, making us aware that actually it should be people, not money, that make the world go round. She implores us, as humans, to question modern day humanity and to rediscover what is important.

Visitors could have been forgiven for thinking that ‘Utopia’ was about dystopia, yet the fact that the experience makes you feel ashamed of our insular and money-driven outlook convinces you otherwise. The work seemed to say ‘surely we can do better than this', and such a world-improving thought is, after all, utopian at its core. As philosopher Herbert Marcuse believed, ‘Art cannot change the world, but it can contribute to changing the consciousness and drives of the men and women who could change the world’. Put more simply by Woolcock: ‘Utopia is possible if we just think differently’.

As you entered the main space sounds reverberating from the projection to the left were disorienting, words crackled around you: ‘moneymaking is all around’, ‘advertising stuff’, ‘money, money, money’. One rioter explained the desire for Nike trainers, and the reality of the situation 4 years ago ‘I can’t afford it and the shop doors were open…’ providing an insight into the minds of the rioters. Another explained the reality of society ‘some people are destined to commit crimes…you create thieves and then punish them for stealing’. At Utopia Live Lates, Arlene Phillips CBE stated that ‘money has become the biggest God on earth’, and it would seem she isn’t too far from the truth.

Utopian thinker William Morris believed that art was ‘the central battleground in the warfare of his age’ and I think that this notion was at play at the Roundhouse. Philosophy was at the heart of the exhibition - not only did its title derive from philosophical roots - but the likes of More’s Utopia and Plato’s Republic could be found in the ransacked library room, and readings from them were heard amongst the many voices. One Londoner spoke of how reading Plato changed his perspective on life after his involvement in the London riots.

Woolcock believes that ‘art is not just decoration…but absolutely central to who we are as human beings’ and her work at the Roundhouse exemplified this. She allowed Londoners to disclose everything - their sex lives, their class and their attitude towards other classes, their depression, their thoughts on gentrification, their experiences of racism, their anxieties, their childhood, the reality of being bullied, their education failures, their shoplifting tales and their laughter. Her work is a critique of our present situation, making us aware that actually it should be people, not money, that make the world go round. She implores us, as humans, to question modern day humanity and to rediscover what is important.

Visitors could have been forgiven for thinking that ‘Utopia’ was about dystopia, yet the fact that the experience makes you feel ashamed of our insular and money-driven outlook convinces you otherwise. The work seemed to say ‘surely we can do better than this', and such a world-improving thought is, after all, utopian at its core. As philosopher Herbert Marcuse believed, ‘Art cannot change the world, but it can contribute to changing the consciousness and drives of the men and women who could change the world’. Put more simply by Woolcock: ‘Utopia is possible if we just think differently’.

“Two of his rooms are bigger than my whole house...wow imagine if I had that"

"People don't know why you feel the way you feel but there are many ways to feel disconnected"

Author: Sarah Moor

Roundhouse, Chalk Farm Rd, London, NW1 8EH

http://www.roundhouse.org.uk/whats-on/2015/penny-woolcock-utopia/

Roundhouse, Chalk Farm Rd, London, NW1 8EH

http://www.roundhouse.org.uk/whats-on/2015/penny-woolcock-utopia/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed