| Japanese electronic composer and visual artist Ryoji Ikeda first came onto my radar last summer thanks to Spectra, his light and sound installation which lit up Victoria Tower Gardens in August. Spectra bore some resemblance to the United Visual Artists Barbican exhibition Momentum of the same year, which used pendulums to choreograph light, sound and movement, distorting the visitors experience of space. Similarly Umbrellium, part of last years Digital Revolution exhibition at the Barbican,allowed participants to shape, manipulate and interact with luminous forms. Preceding the examples above, the 2013 Light Show at the Hayward Gallery showcased the experiential and phenomenal aspects of light like never before, remaining to date one of my favourite exhibitions. The power of light and sound to create atmosphere and shape spaces is clearly not new - it dates back to the 1960s in fact - however Ikeda brings the immersive, sensory experience to the public in unusual ways... |

This is in part due to the removal of his work from the traditional gallery space. Spectra used rays of light to illuminate the floating particles and insects filling the summer evening air surrounding an iconic London landmark. It created an 'other worldly', almost transcendental atmosphere and a sense of peacefulness, whilst allowing visitors to interact with the beams and create their own sounds. His latest show Supersymmetry uses the disorientating black space of The Vinyl Factory’s Brewer Street Car Park to stimulate the senses in a much more intense way, paralysing the eye by the use of strobe lights and using high-frequency sound to destabilise conscious perception.

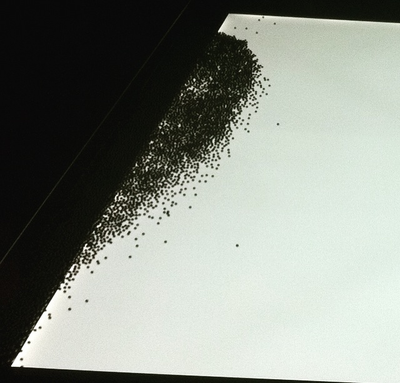

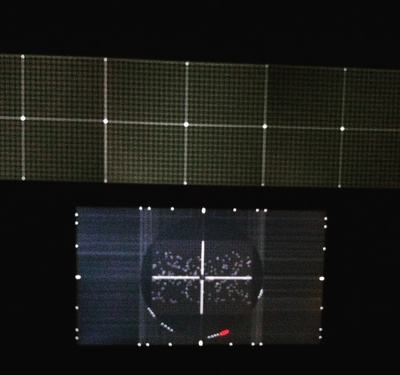

As you move through the darkened space, you are drawn towards tables containing moving ball-bearings, which travel organically like a flock of birds or swarm of bees across the table top. At times your eye follows a stray, solitary ballbearing which breaks free from the pack only to collide back together with it moments later, regrouping to form new shapes. The flash of strobe lights provide snapshots of their journey, and the scanner-like quality of the table top makes it ever more clear that the life of the ball bearings is being examined. The balls are alive, as though part of a physical, chemical or biological make-up.

As they moved across the body of the table my mind imagined they were chemicals in the blood stream. A flash of the strobe light later and the swooshing sounds of their movement transformed them in my imagination to a mass of water, a wave which breaks up and disperses as it crashes against the perimeters of the table. The work continuously takes you to another place, you become transfixed by the way that the balls come together to create shapes and break apart as they meet the edges of their receptacle. Something so simple becomes so absorbing that verges on the hypnotic; you arrive at a sort of peace amidst the chaos of the movement, the noise, the flashes of light.

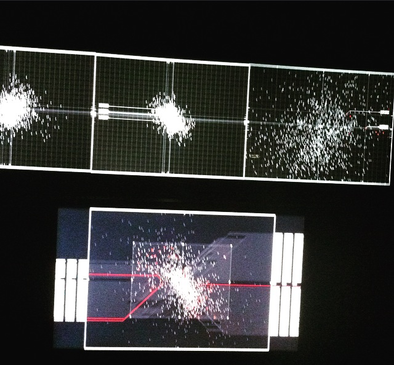

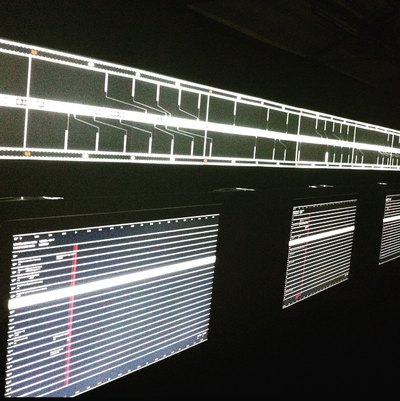

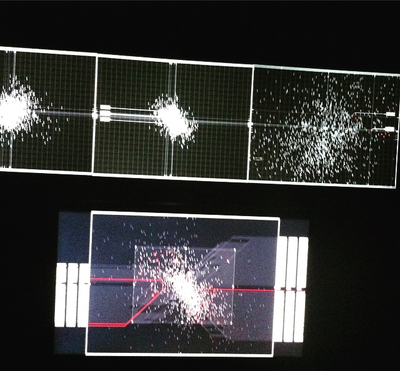

A second room awaits, with two giant screens lining the length of the room, and smaller screens placed in front; not a million miles away from the NASA control room in Michael Bay’s Armageddon. The data is continuously changing, the screens displaying information rich in modern day associations: a computer screensaver, a timeline accompanied by typewriter sounds, random digital stats to the sound of white noise, lists of gobbledygook accompanied by an overhead robotic voice, a hospital heart monitor with the all too familiar electrocardiogram line of life and periodic beeps, data akin to radar/surveillance and increasing dots filling the screen, accompanied by a high pitched almost unbearable buzz. The crescendo of lines and dots of data, along with the continuous static sound of electricity create the feeling that the machines might explode with information at any moment, showing the pace at which information is transmitted digitally. The seemingly uncontrolled recording and data gathering taking place is suggestive of a robot out of control, with the rapid switch from screen to screen almost unbearable to watch. For me, this room symbolises the never ending stream of information generated by the data-driven modern world; sound and vision are engaged by the electric atmosphere in which the data of life is open for analysis.

Afterwards, I read the exhibition synopsis: ‘an artistic vision of the reality of nature, an interpretation of quantum mechanics and quantum information theory from an aesthetic viewpoint’. The beauty of this work, like all art, is the extent to which any number of meanings can be communicated, understood or misunderstood in equal measure. To me, Supersymmetry is the factual counterpart to the spiritual experience of Spectra. Here, the emphasis is on data, physics, chemistry, and the natural flux of life, symbolised through digital means. I read the feedback book as I left the exhibition, and one comment stood out: ‘it’s hard to be overwhelmed these days but today I was’. I had to agree.

Author: Sarah Moor

As you move through the darkened space, you are drawn towards tables containing moving ball-bearings, which travel organically like a flock of birds or swarm of bees across the table top. At times your eye follows a stray, solitary ballbearing which breaks free from the pack only to collide back together with it moments later, regrouping to form new shapes. The flash of strobe lights provide snapshots of their journey, and the scanner-like quality of the table top makes it ever more clear that the life of the ball bearings is being examined. The balls are alive, as though part of a physical, chemical or biological make-up.

As they moved across the body of the table my mind imagined they were chemicals in the blood stream. A flash of the strobe light later and the swooshing sounds of their movement transformed them in my imagination to a mass of water, a wave which breaks up and disperses as it crashes against the perimeters of the table. The work continuously takes you to another place, you become transfixed by the way that the balls come together to create shapes and break apart as they meet the edges of their receptacle. Something so simple becomes so absorbing that verges on the hypnotic; you arrive at a sort of peace amidst the chaos of the movement, the noise, the flashes of light.

A second room awaits, with two giant screens lining the length of the room, and smaller screens placed in front; not a million miles away from the NASA control room in Michael Bay’s Armageddon. The data is continuously changing, the screens displaying information rich in modern day associations: a computer screensaver, a timeline accompanied by typewriter sounds, random digital stats to the sound of white noise, lists of gobbledygook accompanied by an overhead robotic voice, a hospital heart monitor with the all too familiar electrocardiogram line of life and periodic beeps, data akin to radar/surveillance and increasing dots filling the screen, accompanied by a high pitched almost unbearable buzz. The crescendo of lines and dots of data, along with the continuous static sound of electricity create the feeling that the machines might explode with information at any moment, showing the pace at which information is transmitted digitally. The seemingly uncontrolled recording and data gathering taking place is suggestive of a robot out of control, with the rapid switch from screen to screen almost unbearable to watch. For me, this room symbolises the never ending stream of information generated by the data-driven modern world; sound and vision are engaged by the electric atmosphere in which the data of life is open for analysis.

Afterwards, I read the exhibition synopsis: ‘an artistic vision of the reality of nature, an interpretation of quantum mechanics and quantum information theory from an aesthetic viewpoint’. The beauty of this work, like all art, is the extent to which any number of meanings can be communicated, understood or misunderstood in equal measure. To me, Supersymmetry is the factual counterpart to the spiritual experience of Spectra. Here, the emphasis is on data, physics, chemistry, and the natural flux of life, symbolised through digital means. I read the feedback book as I left the exhibition, and one comment stood out: ‘it’s hard to be overwhelmed these days but today I was’. I had to agree.

Author: Sarah Moor

RSS Feed

RSS Feed