| German artist Carsten Höller - ‘the guy that makes the slides’ - is no stranger to London, having installed ‘Test Site’ in the Tate’s Turbine Hall in 2006. Nine years later he’s back, whipping up a media frenzy with his current exhibition ‘Decision’ at Southbank’s Hayward Gallery and triggering the age old question ‘but is it art?!’ from critics and the general public. BBC’s Arts Editor Will Gompertz thinks not, imploring us to question more what is and what isn’t art. With the idea that anything can be art no longer an avant-garde concept, he sees ‘Decision’ as no more than a collection of ‘fairground type rides that happen to be in an art gallery’. The main concern seems to be whether in 2015, contemporary art is being reduced to nothing more than entertainment. However, a recent panel discussion led by Ralph Rugoff, Director of the Hayward Gallery, raised an important point: since when were art and entertainment ever separate? The title of this blog takes inspiration from the very name of this discussion. |

The media certainly portrayed the exhibition as fun, an attraction - albeit in perhaps a surprising location - not to be missed. A blockbuster exhibition with fanaticism wrapped around it, the crowds are inevitably flocking to see and experience the spectacular and interactive show, and the queues for each attraction were certainly reminiscent of my Disneyland days - although this time I wasn’t crying and begging my mum not to take me on Tower of Terror.

Perhaps we should compare Höller’s slide with Rise and Slide, which was situated on King’s Boulevard, Kings Cross a couple of weeks ago. The 100 meter long waterslide would also have been more at home at Thorpe Park rather than central London. So what’s the difference? For a start the purpose; Rise and Slide was part of a promotional campaign for Lipton’s ice tea, purely designed for fun. It wasn’t aesthetically pleasing and it’s form was entirely predictable. Holler’s slide had aesthetic value, the form itself sculpturally beautiful; it was created with an artistic eye, designed to be appreciated by both user and by-stander. It also had a very practical purpose: to serve as the exhibition exit.

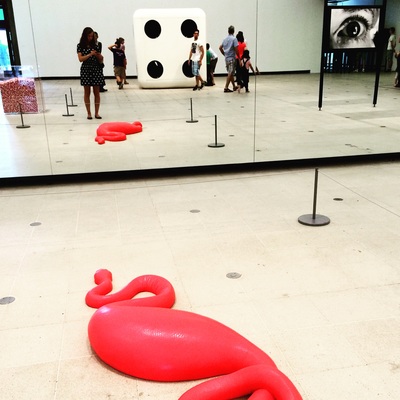

To assume Höller is fobbing us off with cheap entertainment is to deprive him of his due. His objective is to ‘liberate from the dictatorship of the predictable’, creating ‘moments of not knowing’ and allowing the visitor to partake in a ‘decision-making process’ with the option to physically get involved in the exhibition or to spectate. There is much more than fun at play here.

Like Marina Abramovic’s ‘512 Hours’ show last summer, the experience started with putting my belongings in a locker, although this time I could take my phone with me which immediately meant that the lived experience was to be documented and immortalised on social media. I strode past the only signs in the whole exhibition, which warned claustrophobic people to take an alternative entrance, and straight on in through Entrance B. I always had my suspicions that I had claustrophobic tendencies and of course these were confirmed as soon as it was too late. My stride soon became a shuffle as I made my lonely way through a long, winding tunnel which happened to be completely pitch black and pretty damn disorientating. With only the sounds of other visitors feet shuffling and mouths chattering reverberating around the metal structure giving hints to my whereabouts, I had to rely entirely on touch to weave my way out of the tunnels and into the main gallery spaces. By this point I had become increasingly aware of my breathing, had started to sweat, and the words ‘get me out of here’ were still lodged in my throat. Dramatic? I felt not.

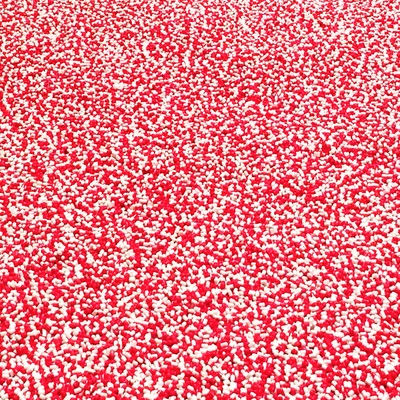

Having survived the tunnel of terror the giant revolving mushrooms had me thinking I was experiencing some kind of drug-induced hallucination whilst at the same time generating a deja-vu-of-sorts with Martin Creeds revolving steel ‘Mothers’ beam, also at the Hayward last year. The pile of pills available for knocking back only added to the feeling of a mad house.

‘The Forests’ oculus rift glasses soon transported me out of the gallery space and into a winter wilderness. By this point I was half expecting something to jump out from between the trees. Instead I started to question whether I needed to go to the opticians pronto as I began to experience blurred vision as the scene in front of me began to split in two and blur. Had I read the exhibition programme first I would have understood that this was Holler’s intent, and not my flawed eyes. He fooled me again.

I thought I knew what I was getting myself into with the upside down goggles which followed - pretty self explanatory I thought. As I queued I heard another visitor say ‘I definitely feel sick after that’ whilst handing her goggles back. I was warned to take it easy, sit down with the goggles on first and see how I felt. I had no idea how disorientating an upside down world could be. As soon as I stood up I began to wobble and genuinely felt like I was going to fall over.

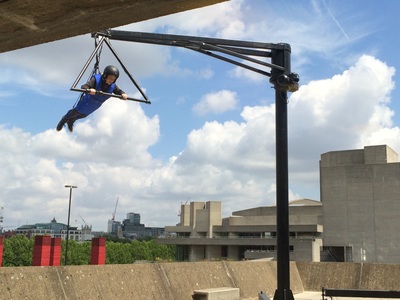

As you might expect I chose not to participate in the flying machine. I told myself the queue was too long…but in reality my decision had everything to do with my fear of heights. Despite this, however, I did make my way up to the roof and exit via the slide, with the speed of the descent forcing air through my lungs, and rather unfortunately up my skirt. I left feeling bemused, adrenaline still pumping through my veins. Taking a stroll down towards the river I saw children squealing in delight as they ran through Jeppe Hein's water fountains under rays of sunshine. That, I thought, is what I call fun.

So if I wouldn’t describe ‘Decision’ as fun, what would I call it? Emotional manipulation, an experiment to explore comfort zones, a ploy to make us realise what we enjoy and what we don’t enjoy. Each element was a mood changer, an opportunity to explore what we fear and what we welcome. As all visitors endure the same experiences but with varied responses, it was an opportunity for sharing, and for bonding.

During the panel discussion mentioned earlier, Nina Powell, Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Roehampton University, questioned the name of Höller’s exhibition. I can’t argue that decision wasn’t pivotal to the show, and at times very welcome, however for me the exhibition was less about decision-making and more about the feeling of unease and uncertainty, which was heightened by my experiencing the exhibition alone.

Ultimately all art is subjective, and the Institution itself is the authenticator, affirming what is and is not art; to an extent a slide is more than just a slide when the institution says so. It seems fitting that the Hayward Gallery, inspired by Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, is housing this particular show.

I don’t for one second believe that ‘Decision’ is not part of the experience economy, but this by no means reduces its value as art. Art has always reflected the culture in which it finds itself, and participatory and immersive experiences are on the rise...we only need to look to Westfield’s recent introduction of virtual reality and oculus rift for evidence of this. Art is merely cashing in on our obsession with the the 'experience’ phenomenon and responding to audiences which are craving for real life experiences which can compete on the same level as digital experiences. Looking is no longer enough, the choice to participate and truly live experience is sought after. As Grayson Perry states: 'In the digital age, you have to actually show up’, and Höller gives us every reason to do so.

Author: Sarah Moor

Perhaps we should compare Höller’s slide with Rise and Slide, which was situated on King’s Boulevard, Kings Cross a couple of weeks ago. The 100 meter long waterslide would also have been more at home at Thorpe Park rather than central London. So what’s the difference? For a start the purpose; Rise and Slide was part of a promotional campaign for Lipton’s ice tea, purely designed for fun. It wasn’t aesthetically pleasing and it’s form was entirely predictable. Holler’s slide had aesthetic value, the form itself sculpturally beautiful; it was created with an artistic eye, designed to be appreciated by both user and by-stander. It also had a very practical purpose: to serve as the exhibition exit.

To assume Höller is fobbing us off with cheap entertainment is to deprive him of his due. His objective is to ‘liberate from the dictatorship of the predictable’, creating ‘moments of not knowing’ and allowing the visitor to partake in a ‘decision-making process’ with the option to physically get involved in the exhibition or to spectate. There is much more than fun at play here.

Like Marina Abramovic’s ‘512 Hours’ show last summer, the experience started with putting my belongings in a locker, although this time I could take my phone with me which immediately meant that the lived experience was to be documented and immortalised on social media. I strode past the only signs in the whole exhibition, which warned claustrophobic people to take an alternative entrance, and straight on in through Entrance B. I always had my suspicions that I had claustrophobic tendencies and of course these were confirmed as soon as it was too late. My stride soon became a shuffle as I made my lonely way through a long, winding tunnel which happened to be completely pitch black and pretty damn disorientating. With only the sounds of other visitors feet shuffling and mouths chattering reverberating around the metal structure giving hints to my whereabouts, I had to rely entirely on touch to weave my way out of the tunnels and into the main gallery spaces. By this point I had become increasingly aware of my breathing, had started to sweat, and the words ‘get me out of here’ were still lodged in my throat. Dramatic? I felt not.

Having survived the tunnel of terror the giant revolving mushrooms had me thinking I was experiencing some kind of drug-induced hallucination whilst at the same time generating a deja-vu-of-sorts with Martin Creeds revolving steel ‘Mothers’ beam, also at the Hayward last year. The pile of pills available for knocking back only added to the feeling of a mad house.

‘The Forests’ oculus rift glasses soon transported me out of the gallery space and into a winter wilderness. By this point I was half expecting something to jump out from between the trees. Instead I started to question whether I needed to go to the opticians pronto as I began to experience blurred vision as the scene in front of me began to split in two and blur. Had I read the exhibition programme first I would have understood that this was Holler’s intent, and not my flawed eyes. He fooled me again.

I thought I knew what I was getting myself into with the upside down goggles which followed - pretty self explanatory I thought. As I queued I heard another visitor say ‘I definitely feel sick after that’ whilst handing her goggles back. I was warned to take it easy, sit down with the goggles on first and see how I felt. I had no idea how disorientating an upside down world could be. As soon as I stood up I began to wobble and genuinely felt like I was going to fall over.

As you might expect I chose not to participate in the flying machine. I told myself the queue was too long…but in reality my decision had everything to do with my fear of heights. Despite this, however, I did make my way up to the roof and exit via the slide, with the speed of the descent forcing air through my lungs, and rather unfortunately up my skirt. I left feeling bemused, adrenaline still pumping through my veins. Taking a stroll down towards the river I saw children squealing in delight as they ran through Jeppe Hein's water fountains under rays of sunshine. That, I thought, is what I call fun.

So if I wouldn’t describe ‘Decision’ as fun, what would I call it? Emotional manipulation, an experiment to explore comfort zones, a ploy to make us realise what we enjoy and what we don’t enjoy. Each element was a mood changer, an opportunity to explore what we fear and what we welcome. As all visitors endure the same experiences but with varied responses, it was an opportunity for sharing, and for bonding.

During the panel discussion mentioned earlier, Nina Powell, Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Roehampton University, questioned the name of Höller’s exhibition. I can’t argue that decision wasn’t pivotal to the show, and at times very welcome, however for me the exhibition was less about decision-making and more about the feeling of unease and uncertainty, which was heightened by my experiencing the exhibition alone.

Ultimately all art is subjective, and the Institution itself is the authenticator, affirming what is and is not art; to an extent a slide is more than just a slide when the institution says so. It seems fitting that the Hayward Gallery, inspired by Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, is housing this particular show.

I don’t for one second believe that ‘Decision’ is not part of the experience economy, but this by no means reduces its value as art. Art has always reflected the culture in which it finds itself, and participatory and immersive experiences are on the rise...we only need to look to Westfield’s recent introduction of virtual reality and oculus rift for evidence of this. Art is merely cashing in on our obsession with the the 'experience’ phenomenon and responding to audiences which are craving for real life experiences which can compete on the same level as digital experiences. Looking is no longer enough, the choice to participate and truly live experience is sought after. As Grayson Perry states: 'In the digital age, you have to actually show up’, and Höller gives us every reason to do so.

Author: Sarah Moor

RSS Feed

RSS Feed